This is not so much a review as a guide to anyone just starting out with single malt Scotch. A large liquor store may have up to 100 different single malts and in total there have been over 1500 brands which makes a newcomer feel lost. Unlike bourbon or brandy or a particular wine like sauvignon blanc the various Scotches are completely different. There is very little useful guidance; most review sites appear to like every kind of Scotch which doesn’t help much in choosing your first couple of bottles. If you ask random Scotch drinkers they will recommend something like Talisker or Glenrothes or Laphroaig, which you may or may not like, but it won’t help much at the store when you look for the next bottle to try. I’ve found that choosing at random is a bad idea.

A little quick background will help you understand some of the differences. For millennia Scotland has been a very poor country. Most of the Scotch distilleries today started out as illegal bootleg stills in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s with limited access to resources. Scotch is made from malted barley like beer without the hops. The barley is moistened to allow it to just germinate (malt) and then is dried with heat to stop the malt. Here is the first problem; most of the trees in Scotland were cut down hundreds of years ago for firewood. The usual solution is to dig up peat from various bogs and fens and burn it which dries the barley but also adds often strong flavors that vary by local. The malted barley is mixed with water in vats and allowed to ferment producing ethanol. The result is distilled multiple times. The water comes from a local stream or lake which adds its own flavors. Most operations were set up near streams with particularly suitable water. The raw alcohol from the still is not drinkable and needs to be aged in wood casks as is the case for most distilled spirits. Here is the next problem; new casks were too expensive for the Scots to afford. The solution was to buy used Kentucky bourbon casks from America or used sherry casks from Spain.

The use of peat, coal, or other fuel for process heat, the type and handling of the Barley, the water source, the details of the stills, the second fill casks used for aging, and even the conditions in the cask house affect the taste of the final product.

By Scottish law Scotch must be aged in the cask for at least 3 years. As a practical matter commercial Scotch is almost always 8 or more years old. The “age” refers to the time spent in the wood casks. Once bottled, the Scotch stops aging. The older Scotches are not just batches that were left longer in the casks. They are individual barrels that were identified by the Master of Malt or equivalent at an early stage as especially promising and held for a longer aging cycle. There may only be a few casks a year good enough to benefit from aging for 18 or 25 years. A 40 or 50 year old Macallan candidate cask may only be identified once in a decade or so. The price has nothing to do with taking up space in the warehouse and everything to do with a very limited supply of a great whisky.

The most distinctive discriminant of Scotch flavors is the taste described as smokey, peaty, medicine, or iodine produced by phenols from the peat and possibly sea air. This taste ranges from very strong in Scotches like Laphroaig to nonexistent in Auchentoshan and Glengoyne which don’t use peat in their process.

By the way, bourbon is whiskey, Scotch is whisky. Many single malt brands peak in terms of interesting flavor in the 15 to 18 year range. Younger malts are a little rough and older Scotches seem to pick up more flavors from the cask than from the original process. For instance I like Macallan 18 ($300) better than Macallan 25 ($1700) and the Macallan 15 ($140) is perfectly nice. On the other hand while Glenfarclas 17 ($85) is good, Glenfarclas 25 ($160) is wonderful. Scotch snob warning: While the Scots usually put a little water in their Scotch, the custom elsewhere is to drink it neat and at room temperature. If you drink it with ice or even in a chilled glass the cold ruins the taste you paid for. The Scots also use single malts for cocktails. It makes me shudder but I suppose that’s what they have. If you want a Rusty Nail, a Rob Roy, or a Godfather use a blend like Chivas, Johnnie Walker, or Dewar’s and don’t waste your single malt investment.

Like wines in France, Scotland has several Scotch regions with their own typical character. Unlike French regions where all the white Bordeaux from the Entre-Deux-Mers region is similar, Scotches from each region can vary widely.

Islay is an island west of the mainland and home to Ardbeg, Lagavulin, Laphroaig, Bowmore, and Bruichladdich (bruke-laddee) most of which are strongly peated. Laphroaig prides itself as “The most richly flavored of all Scotch whiskys” and is very smoky. Talisker is another highly peated Scotch from the Isle of Skye that reportedly gets its character from the sea environment.

Campbeltown is on the Kintyre peninsula near Islay which once had 30 distilleries. It is now known for brands like Springbank, Hazelburn, and Glen Scotia. These are somewhat smoky but less distracting than the Islay malts.

The lowland malts like Auchentoshan are very mild. It features the tallest stills of any distillery which may account for the smoothness. Glengoyne 18 is very flavorful in an interesting fruitly way and one of my favorites. It prides itself as being unhurried since 1833, and “the patience we take over the slowest distillation in Scotland”. (It’s also the closest distillery to my ancestral home.)

The highland malts are separated into Speysides just south of Moray Firth and the rest of the highlands. Speysides are very drinkable mostly with limited peat. Some of the most recognizable brands are Glenlivet, Glenfiddich (-dik), Longmorn, and Macallan. The Glenfiddich 18 is very smooth while retaining some character. The Glenlivet verges on bland and since most chain restaurants just carry Glenlivet and Glenfiddich , I always pick the Glenfiddich for the better finish. Recently Glenlivet moved to perk up their offerings by coming out with a 15 year French Oak Reserve aged in NEW French oak barrels. This makes a big difference and produces a really rich fruity flavor. Others have copied this like Balvenie and Glen Garioch (geery) with less successful results. Macallan has been rightly described as the Roll-Royce of Scotches. Their products are consistently good with rich flavors, low smoke, and the traditional long finish. While I usually drink the 15, they have started coming out with annual limited edition versions and the most recent, number 4, is perhaps the best Macallan I’ve tasted yet. Macallan only uses the first 16% of the ethanol that distills off the barley mash in their whisky. Distilling for too long produces higher alcohols and other impurities. Macallan is willing to waste more mash than some for a superior product and is able to charge more to cover the cost. Longmorn is a good pick but hard to find. The Scotches I like have a nice aroma and Aberlour A’bunadh has one of the nicest and most intense. It is bottled at cask strength, 120 proof, and is intended to be mixed 4 parts Scotch to 1 part distilled water to bring it down to 86 proof for drinking. Don’t cheat here: the distilled water makes a big difference. It doesn’t work right with bottled drinking water. The Glenrothes 15 is good but smoky enough to take some getting used to. A note here is that the way you are feeling, how tired you are, or what you’ve been eating has a surprising effect on how a given Scotch tastes on a given day. The complexity of some like Glenrothes is more sensitive to this than some others.

Glenfarclas is one of the few privately owned family distilleries in Scotland. It is currently being operated by the 6th descendant of the original owner. He is selling Scotch that his grandfather distilled and is distilling Scotch that his grandchildren will be selling. He takes very great care with what he leaves to them. The Glenfarclas 17 is tasty; but as I mentioned before, the 25 is wonderful and at $160 it is far more accessible for drinking purposes than the 25 year old Macallan at $1700.

There are over 40 Speyside distilleries that overshadow the 30 or so other highland products but some of the latter are very interesting. Oban on the Firth of Lorn in the west highlands is good but fairly smoky. Scapa and Highland Park are only about 5 miles apart on the Orkney Islands north of the Scottish mainland but are completely different. Scapa is a very smooth Scotch similar to some lowlands brands while Highland Park is more like the heavily peated Islay Scotches. Macduff which produces Deveron is the easternmost operating distillery in the highlands. The Deveron 18 is excellent with a nice finish and is not too smoky. Dalwhinne is the highest distillery in Scotland — if nothing else their stills boil at the lowest temperature of any in Scotland. Their whisky is very smooth even if slightly smoky and is known as “the gentle spirit”.

My current favorite is Glen Morangie 18 (rhymes with orangy). It has a very nice rich fruity flavor, good finish, and is very smooth. When I started on single malts, Glen Morangie prided itself as being a small local operation with their whisky “Handcrafted by the 16 men of Tain” for decades. Tain is a village on the south side of Dornoch Firth about 25 miles north of Inverness. In the past 30 years Glen Morangie has justifiably become very popular and grown accordingly. While they still keep the original small distillery running, they have become a major producer and their bottles now say “Perfected by the 16 men of Tain”. The end product is as good as ever.

Some other good choices: Lismore 18, a very smooth yet inexpensive Speyside whisky, Aberfeldy 18, a richly flavored highland whisky with only the slightest hint of smoke in the finish (their 16 year old is almost as good), and Aberlour 18, another Speyside – perhaps the most richly flavored non-peated scotch, even more so than their A’bunadh. Unlike Aberfeldy, the 18 year Aberlour is much better than the 16 and the price reflects this. Shieldag 18 is very smoth and surprisingly economical. The Tamdhu 12 and 15 are also excellent and reasonably priced.

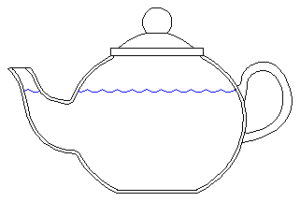

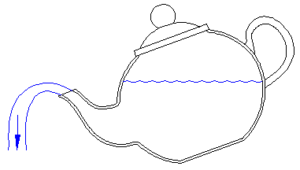

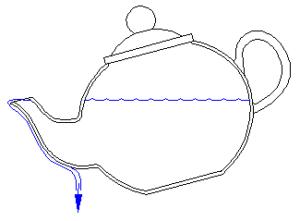

Here is a Wikimedia map of the distilleries in Scotland.

Automated attacks engender wards : Please leave comments, friend, using the post in my comments category.